Blog

“I feel the need, the need for speed” - Agile Development and the Lockheed “Skunk Works®”

The key to success in developing a new product and delivering

it to market is “ Speed of Learning“. How the information

needed to demonstrate that the product does what it’s supposed

to do is acquired (by test or analysis) as quickly and

efficiently as possible in order to support verification and

validation, decision making and progress toward an in-service

product. These days a lot is made of "agile development"

principles that has been espoused mainly by the software

industry in recent years. It is however universally applicable

to any complex product development programme. To me, agile is

a digital era re-branding of how things used to get done in a

pre-digital age where iterative physical testing with limited

computing capability was the only way to get a complex product

or system ready for customer delivery.

The dictionary defines the word “agility“ as:

- The power of moving quickly and easily; nimbleness.

- The ability to think and draw conclusions quickly; intellectual acuity.

Agile development is all about setting up your organisation to

achieve both these things. Ultimately it’s about ensuring you

can do things quickly, be able to change direction when

required and reach required decision points in a logical order

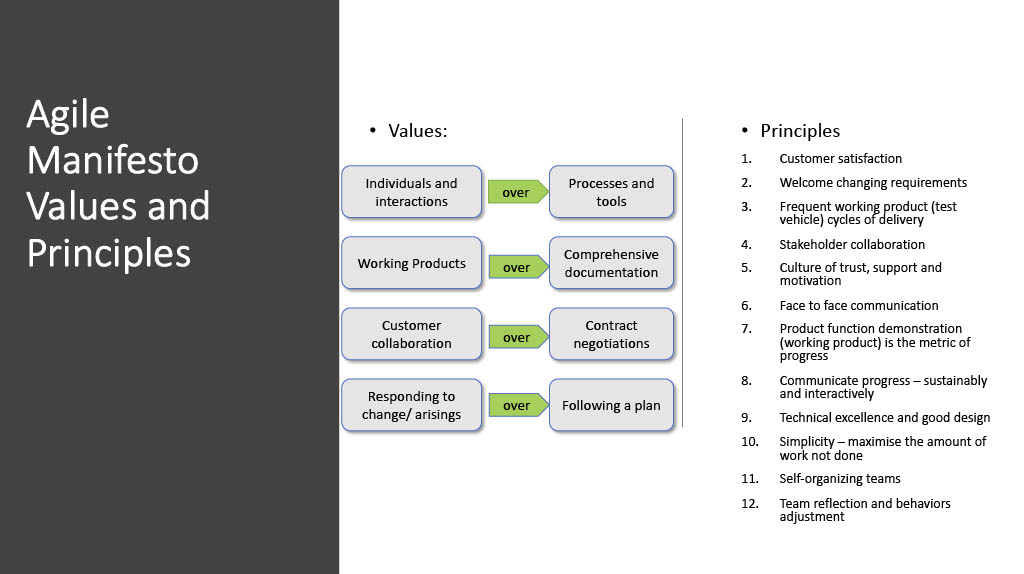

and move on. The values and principles of the “agile development manifesto” are given below. All are needed in order to run effective

and timely development programmes:

The "Agile Manifesto" values and principles

Ben R. Rich “The Father of Stealth” and the F-117 Nighthawk fighter

In my opinion, the best demonstration of agility was the

operation of the

Lockheed

Skunk Works® originally run by one of my heroes, Kelly Johnson

(see last blog). The philosophy that dictated how the Skunk

Works® was run was KISS - Keep It Simple, Stupid! That along

with following mantras like "fail fast, learn quick” produced

some incredible results in unbelievably short lead-times. The,

U2

and

SR-71

reconnaissance planes and the

F-117

stealth fighter were some of the products developed through

the Kelly Johnson instituted 14 “rules” for running the Skunk

Works® which are reproduced below with the key points in bold.

Remember this is for an organisation producing aircraft for

military application - I trust you will interpret them in the

context of your own industry/ market.

- The Skunk Works® manager must be delegated practically complete control of his program in all aspects. He should report to a division president or higher.

- Strong but small project offices must be provided both by the military (customer) and industry.

- The number of people having any connection with the project must be restricted in an almost vicious manner. Use a small number of good people (10% to 25% compared to the so-called normal systems).

- A very simple drawing (design) and drawing release system with great flexibility for making changes must be provided.

- There must be a minimum number of reports required, but important work must be recorded thoroughly.

- There must be a monthly cost review covering not only what has been spent and committed but also projected costs to the conclusion of the program.

- The contractor must be delegated and must assume more than normal responsibility to get good vendor bids for subcontract on the project.

- The inspection system as currently used by the Skunk Works, which has been approved by both the Air Force and Navy, meets the intent of existing military (customer) requirements and should be used on new projects. Push more basic inspection responsibility back to subcontractors and vendors. Don't duplicate so much inspection.

- The contractor must be delegated the authority to test his final product in flight. He can and must test it in the initial stages. If he doesn't, he rapidly loses his competency to design other vehicles.

- The specifications applying to the (development) hardware must be agreed to well in advance of contracting. The Skunk Works practice of having a specification section stating clearly which important military specification items will not knowingly be complied with and reasons therefore is highly recommended.

- Funding a program must be timely so that the contractor doesn't have to keep running to the bank to support government projects.

- There must be mutual trust between the military (customer) project organization and the contractor with very close cooperation and liaison on a day-to-day basis. This cuts down misunderstanding and correspondence to an absolute minimum.

- Access by outsiders to the project and its personnel must be strictly controlled by appropriate security measures.

- Because only a few people will be used in engineering and most other areas, ways must be provided to reward good performance by pay not based on the number of personnel supervised.

There are clear similarities between the two. Whilst many

organisations get the agile development approach right, there

are three key damaging traits that can creep in that can

compromise the approach. The first is highly detailed,

inflexible planning in far too fine a level of fidelity.

Whilst good planning is essential, it needs to be focussed on

achieving the cardinal decision points not every minute step

along the way.

Colin Powell is quoted as saying; “There are no secrets to

success. It is the result of preparation, hard work and

learning from failure”. He, amongst others also re-quotes a

saying; “No plan survives first contact with the enemy”. This

simply acknowledges that you cannot fully plan for a fluid

situation. In the case of development of a complex product or

system, we do not know what issues will arise, only that some

inevitably will. In this case the plan has to address the key

programme intentions (e.g. demonstrate cardinal functionality

traits) in the right order. Good risk assessments of the

design and the programme help develop a view of the most

likely and most damaging issues that may be encountered and

thus "plan b and c" flexibility built in as acceptable

directions of travel. These become the issues that the plan

needs to address in this manner. The only certainty is that

the original plan will not be executed in the detailed way it

was intended. In the face of unpredictability, we need

adaptability. To be less subtle about it, sh*t will happen and

the organisation needs to be able to deal with it!

The second trait is processes that are too detailed and

constraining. That is, the work processes are so rigid,

progress is hampered by dotting every i and crossing every t

in a very prescribed manner. Steve Jobs once said, “We don’t

hire smart people to tell them what to do; we hire smart

people so they can tell us what to do”. Add that to a third

trait, over zealous governance, and the whole approach breaks

down as several of the key principles of “Agile" get destroyed

as a result. Self-organising teams no longer feel self

organised, the culture of trust, support and motivation is

undermined and adjustment following reflection is constrained.

The "practically complete control” of the leader is also

compromised.

The impact of breaking the people principles are most damaging

to team cohesion and thus delivery. Progress gets bogged down

with details that aren’t essential, programme reviews get into

far too much detail, the way the work gets done is inflexible

and in the worst cases “tick box" exercises and frustration

rapidly sets in. More resource then get thrown at the project

in an attempt to keep up with milestones and focus gets lost

as the size of the task becomes unwieldy.

In my opinion, the ultimate manifestation of the Skunk Works

approach was in establishing the critical functionality of the

F-117 Nighthawk stealth fighter (i.e that it was invisible to

radar) as quickly as possible. This was just into Ben R Rich’s

tenure in charge (he had taken over from Kelly Johnson having

been mentored by him). In the book "Skunk Works: A Personal

Memoir of My Years at Lockheed”* there is a great description

of how, having computer modelled radar profiles for aircraft

shapes that they went on to build scale wooden models that

were used in an electromagnetic chamber and then mounted on a

pole in the desert to validate the modelling and verify that

the profile was to all intents and purposes invisible to

radar. Having established the shape, everything about the

aircraft requirements and its design had to be flexible to

cope with restrictions placed to ensure that “invisibility”

was never compromised. For a revolutionary aircraft, the time

from letting the contract in 1977 to customer acceptance and

entry into service in 1982 was stunningly fast. What was more

amazing was that the existence of the aircraft was not

publicly acknowledged until 1988 after it had been deployed in

several combat campaigns! To me there is no doubt that the

Skunk Works didn’t fall into any of the traps mentioned above

in executing the F-117 programme.

Model Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk fighter wooden model on radar profile testing in the desert.

How does your business match up to the Agile Development

principles and/or rules on the “Skunk Works”? Are you taking

the right approach to your product development programme

execution and making the best of your smart employees? Do you

need any help in setting up a complex development programme or

establishing capability to let you execute? Feel free to get

in touch to discuss any requirements you may have. Thank you

for reading this blog, I hope you enjoyed it. The next blog

will be “It’s all about the data” - why test is a means to an

end.

* "Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed” by

Ben R. Rich and Leo Janus is another recommended and

inspirational read (available here

or elsewhere) whether you are generally interested in aircraft

or how to get things done in the most complex of cases.